The Brightness of Light: The Muses, the Artists and the Letters

by Vittoria Benzine

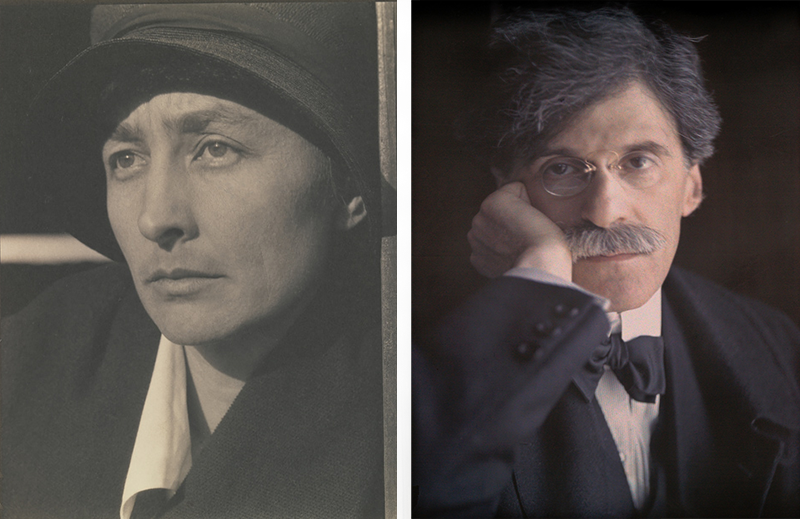

It’s easy to feel like art history happens as if it were the weather. Roving winds from Africa birthed Cubism. A high pressure system in Europe yielded Dada. This well-intentioned take on art overlooks the human element, however. What aesthetics would surround our lives today if Andy Warhol never met Jean-Michel Basquiat, or if Alfred Stieglitz never met Georgia O’Keeffe?

O’Keeffe and Stieglitz initially connected 109 years ago via letters — the famed linchpin of their storied, saucy relationship. The couple exchanged 5,000 letters across 25,000 pages between the time they met, in 1916, and Stieglitz’s death, in 1946. Since then, perspectives on their union have shifted significantly. For several decades, it seemed reasonable to believe there’s no way O’Keeffe, an unknown artist, would have achieved international acclaim without the exposure afforded by her marriage to Stieglitz, who was the most important gallerist, publisher and photographer in American art at the time, single-handedly championing modernism in the States.

O’Keeffe, in turn, became the mother of American modernism, contributing a style all her own to the art-historical canon — at once dreamy, natural, mythic and powerful. She knew the nation better, after all. Whereas Stieglitz was a rich Manhattanite with a European education, an ego and an allowance totaling nearly $4,000 a month, O’Keeffe was a Wisconsin-born daughter of dairy farmers who studied art in Chicago, New York City, Virginia, South Carolina and Texas.

She’d certainly heard of Stieglitz along the way, particularly while at Columbia University and the Art Students League of New York — which awarded O’Keeffe tuition to its summer school in Lake George (where the Stieglitzes summered) after her still life of a dead rabbit won a competition.

In 1893, when O’Keeffe was five years old, Stieglitz — nearly 30 — became a co-editor at the American Amateur Photographer magazine. The photo printing business his father bought him handled all imagery for the magazine. He wed Emmy Obermeyer, the sister of his associate. Over the next five years, Stieglitz led two prominent photography clubs, transforming the newsletter for one into the groundbreaking photography magazine Camera Notes, which he helmed. Stieglitz made it his mission to elevate photography, his great love, to the art-historical importance of painting.

Stieglitz founded the Photo-Secession movement in 1902, then staged the member artists’ first exhibition in 1905 at his new gallery, 291 — catapulting both the movement and the space to renown. 291 later offered seminal American shows to revolutionary artists like Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse and Auguste Rodin.

O’Keeffe was 18 and studying at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago when 291 opened. Seven years later, she learned to appreciate Japanese compositional techniques through a University of Virginia professor who taught her about the artist Arthur Wesley Dow. In 1914, she studied directly under Dow at Columbia University — then started teaching there in 1915.

In early 1916, O’Keeffe sent her friend, the suffragist Anita Pollitzer, a few new charcoal abstractions called “Specials.” Pollitzer brought them to 291. Stieglitz famously called them the “purest, finest, sincerest things.”

O’Keeffe made her first contact with Stieglitz soon after. “If you remember for a week — why you liked my charcoals that Anita Pollitzer showed you — and what they said to you — I would like to know,” she wrote him in January 1916, adding that she made them “to express myself — things I feel and want to say — haven’t words for.” With Stieglitz, however, she learned to be very poetic.

Upon her death in 1986, O’Keeffe’s letters joined Stieglitz’s papers at Yale, completing the archive of correspondence — with a stipulation not to publish them for 20 years. From this cache emerges a torrid if common love story. Time moves fast, but people change slowly. At the start of their tempestuous romance, O’Keeffe was 28 and Stieglitz was 52. He had much to offer her professionally. Meanwhile, her benefits to him, besides her beauty, were a bit more abstract.

Society has struggled to make sense of such romantic power imbalances. Although there was an age gap between them, both were grown, more-than-willing adults. As evidenced throughout their letters, they truly loved each other. But, they were both fallible, too.

O’Keeffe — driven yet insecure, that time-honored combination — clearly reveled in her mentor’s admiration. “I am so glad they surprised you,” she wrote to Stieglitz weeks later. “I am glad I could give you once what 291 has given me many times.” Her revelry reinforced his self-image. Legend has it that O’Keeffe had a crush on Stieglitz’s colleague, the photographer Paul Strand, first. When Strand mentioned letters between himself and O’Keeffe, Stieglitz confessed he fancied O’Keeffe, clearing his lane.

In fact, Stieglitz loved O’Keeffe’s vision so much that he showed 10 charcoal drawings at 291 without her permission, O’Keeffe learned from a friend. He misnamed her “Virginia.” O’Keeffe surprised Stieglitz by showing up at her first 291 solo show the following May. “How I wanted to photograph you,” Stieglitz wrote right after she left. “But I didn’t want to break into your time.”

291 closed that year. Their letters heated up, became explicit. In 1918, Stieglitz invited O’Keeffe to live in New York, promising her a quiet studio — if not domestic bliss. “Coming may bring you darkness instead of light,” he wrote before she left, warning that he didn’t know what he wanted from her. “It’s in Everlasting light that you should live.” Stieglitz knew he couldn’t be a provider.

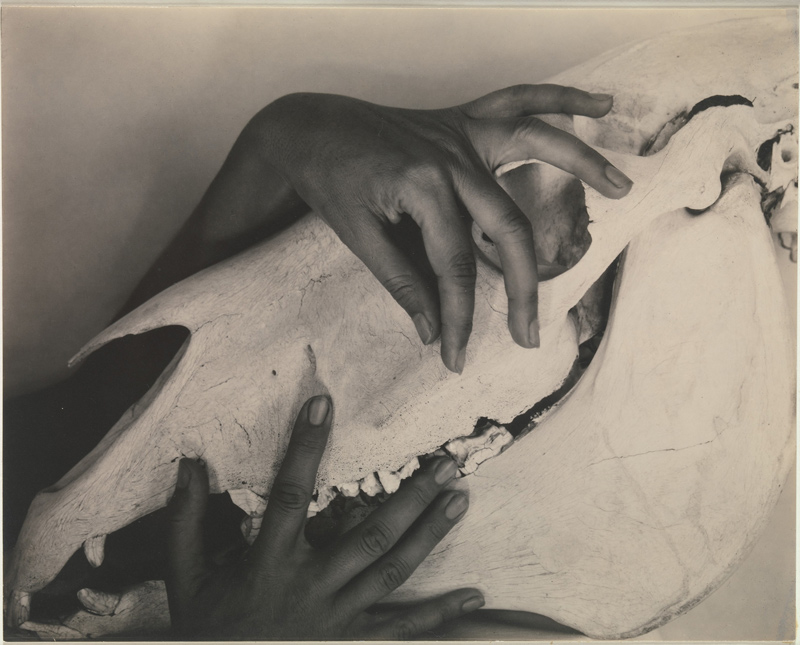

O’Keeffe arrived, and Stieglitz finally got his lens on her, igniting a 350-part series immortalizing her body, often nude. Stieglitz’s wife, Emmy, walked in on an early session. Emmy never had the head for culture he did, but still shared her allowance with him, hopeful she and their now 20-year-old daughter would earn his love someday. Stumbling in on Stieglitz photographing O’Keeffe ripped off those rose-tinted glasses. Emmy told him to stop seeing O’Keeffe, or leave their house.

He chose the latter. One month later, Stieglitz and O’Keeffe were living in Manhattan like newlyweds, making love and making art. Stieglitz may have offered O’Keeffe an enhanced degree of entry into the male-dominated art world, but she unlocked unseen artistic abilities within him. Up until Stieglitz started photographing her, he’d been heralded a far more effective organizer than artist. In 1921, though, Stieglitz got his first solo show in eight years, at Anderson Galleries. Forty-six never-before-seen photos of O’Keeffe debuted — and caused a buzz. These arousing clusters of close-up shots of her body tantalized, in no small part, due to O’Keeffe’s enigmatic personage. The next year, she started incorporating her signature flowers into her paintings, beginning a long and often combative dialogue with critics who viewed them as sexual.

Stieglitz’s divorce from Emmy was finalized in 1924. He wed O’Keeffe soon after, hopeful that the stability would help his daughter’s mental health. O’Keeffe loved him enough to acquiesce, even though she knew Stieglitz had already made moves on confidantes like Strand’s wife Beck (who O’Keeffe is believed to have bedded years later) and O’Keeffe’s sister Ida (who’d declined.)

Marriage bore down. O’Keeffe wanted a child, but Stieglitz had watched his daughter suffer, and he feared his ineptitude as a parent. O’Keeffe got restless summering at Lake George. In 1925, Stieglitz founded The Intimate Gallery. Two years later, a beautiful, young, married Smith graduate named Dorothy Norman started hanging around. Her relationship with Stieglitz began in 1928 — the same year O’Keeffe lost a mural commission for Radio City Musical Hall and was hospitalized for depression. O’Keeffe visited New Mexico with Beck Strand at the behest of a famed patron the following summer, just before Stieglitz opened his largest gallery, An American Place. By 1930, Norman was Stieglitz’s new muse. O’Keeffe started frequenting New Mexico in 1934.

O’Keeffe and Stieglitz exchanged letters all the while. He mourned her absence. At times, she got angry: “I know that one can not control what one feels but one can control the public exhibition of it,” O’Keeffe wrote in July 1934. But, through it all, she wholeheartedly assured Stieglitz she loved him, that separation was best for both of them. She begged him to take care of himself — and understand that without pursuing her work, there would be no “her” to enjoy. “You really need have no regrets about me,” she wrote from Taos in July 1929. “You see — I have not really had my way of life for many years.” Stieglitz responded that he’d love her forever. He’d taken her virginity, after all. In her letters, O’Keeffe called New Mexico “my country.” The desert was her loyal lover. When Stieglitz died in 1946, O’Keeffe kicked Norman out of the hospital room.

For women, this story has never been anything new. The distinct dynamics of gender, work and art at play in this tale between O’Keeffe and Stieglitz, however, feels truly modern. Would there be an O’Keeffe without Stieglitz — or a Stieglitz without O’Keeffe? Probably. Both artists were so fixated on their professional aims that they’d have made themselves happen somehow. But the specific union of these two talents alone left an indelible impact on art history. Therein lies an argument for embracing love as an element of art and work, no matter what pain it may bring.