Reflections of the Anthropocene: River, Rain and What Remains

by Gabriela Godinez Feregrino

From ancient Greek pastoral literature to Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons to oil paintings like Frida Kahlo’s “Naturaleza Viva,” nature’s simultaneous fierceness and tranquility has been a source of infinite artistic inspiration.

The word “Anthropocene” was initially created to categorize the period in time when humans have been the largest influence on the natural world. It was coined by atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen in 2001 as a proposed geological epoch, though, in 2024, the International Union of Geological Sciences voted against ratifying the Anthropocene as a formal geological term. However, the IUGS included in their published statement that the term has expanded into other disciplines such as “social scientists, politicians, and economists, as well as the public at large,” and as such, “it will remain an invaluable descriptor

in human-environment interactions.”

For artists like Renée Fleming, the term offers a lens to contemplate our relationship with environmental destruction and climate change. Fleming’s album Voice of Nature: the Anthropocene is described as a work that “explores nature as both inspiration and a casualty of humanity.”

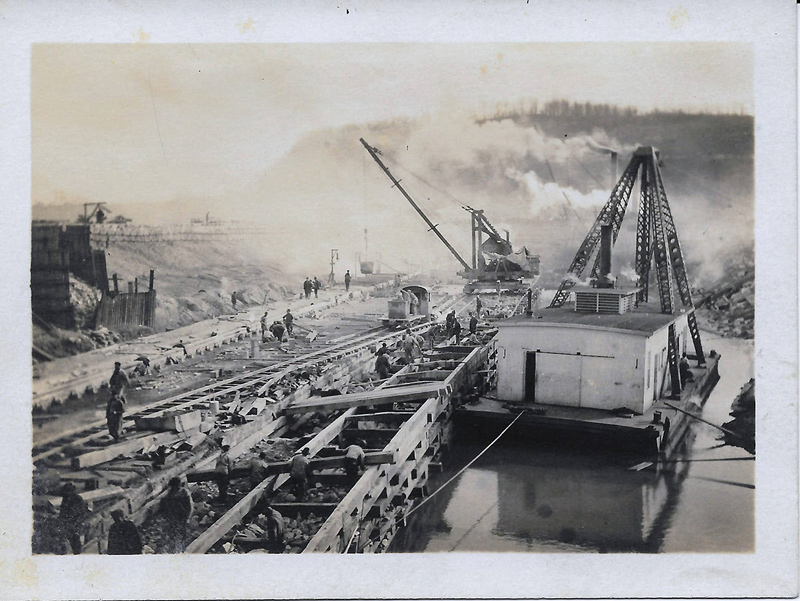

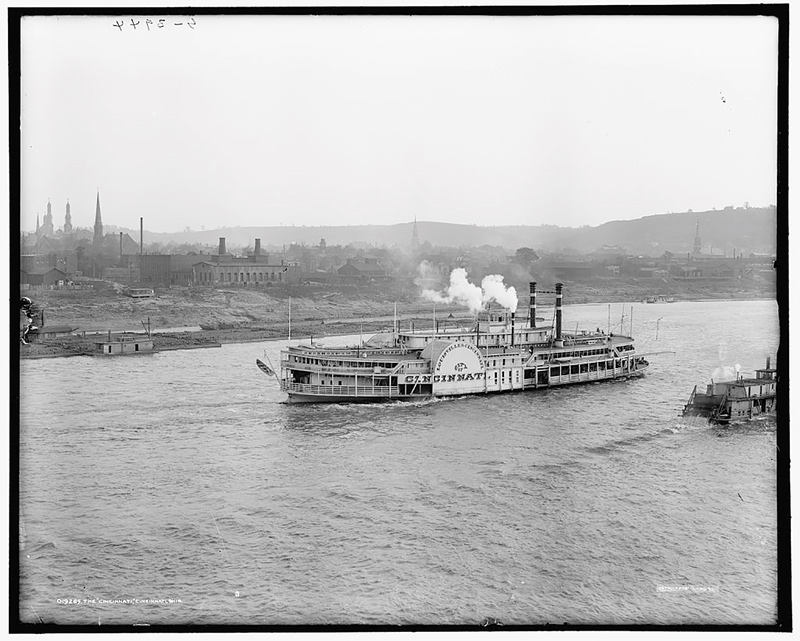

The effects of human-caused climate change are all around us. The Natural History Museum in London states, “Carbon dioxide emissions, global warming, ocean acidification, habitat destruction, extinction, and wide scale natural resource extraction are all signs that we have significantly modified our planet.” Locally, Boone County’s Natural Areas Technician Sarah Grote noted the Ohio River as a prime example of our influence on nature. “The Ohio is a lot different now. It’s no longer a free-flowing river, more like a series of interlocking moving lakes because of all the locks and dams.” They explained that, before human intervention in the 1880s, “the river actually used to be a lot smaller, though it also used to have bigger floods.”

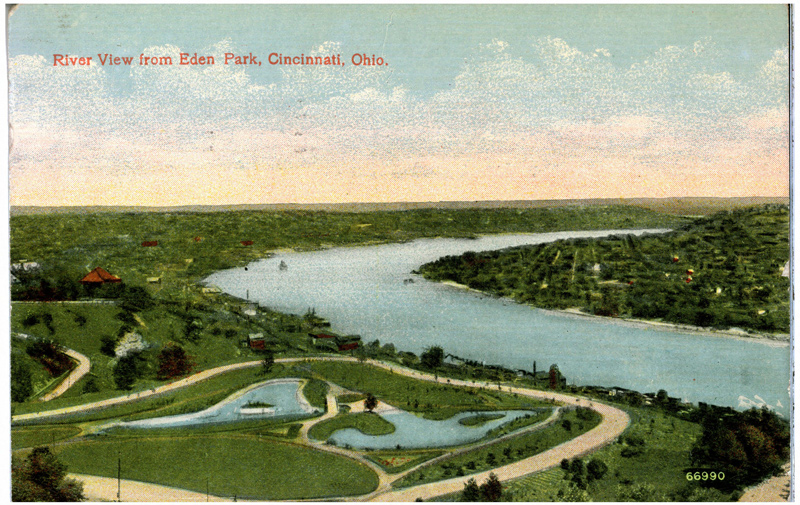

Grote grew up by the river, watching the fog unfurl over it in the mornings. It isn’t difficult to see why the Ohio River has been the subject of so much art throughout the years. Artists like Thomas Hart Benton and writers like Toni Morrison have captured the Ohio River’s unforgiving strength and its beautiful promise of life and freedom.

A sustaining force and a witness to generations of triumphs and tears, the Ohio River holds the hearts of those who live along its shores and deserves protection. Once cared for through generations of rich education by indigenous peoples like the Wahzhazhe Manzhan, Shawandasse Tula and Myaamia, the river became exploited and has suffered extensive pollution through colonialism and industrialization. Today, indigenous peoples continue to advocate for “the critical connection between native sovereignty and environmental preservation.”

Over time, community activism has led to policy reform to restore the river’s health, though the battle is far from over. In 2020, according to Louisville Public Media, “41 million pounds of toxic pollution were released into the Ohio River Basin.” In 2024, the Ohio River Foundation endorsed the Ohio River Restoration Program Act in Congress that aims to restore the Ohio River watershed, benefiting over 30 million people across 14 states. It is important that legal policy like this protects our environment beyond what we are capable of as individuals. This legislation would establish the Ohio River National Program Office and lead restoration efforts and workforce development to ensure clean water access and protection for the region’s communities.

Conserving what nature we have left is vital. Traditional conservation rhetoric often treats nature as something separate from humanity, to be protected from human influence. However, we must go beyond preservation and engage in stewardship, embracing our responsibility in shaping our environment for the future. Grote says, “In this region, we can’t leave land alone. It might be a nice thought to buy land to keep it from being destroyed by a commercial project, but without stewardship, invasive species will overtake the area.” Half-jokingly, Grote said, “It’ll probably become entirely bush honeysuckle.”

Grote encourages people to participate in the rehabilitation of degraded environments but emphasizes sustainable resource use as a more accessible goal. Small habits can have a big impact. We cannot detach ourselves from nature. We must think of ourselves as an active part of it and reckon with our responsibilities.

Our ancient connection with nature is deeply intertwined with our well-being. Today, we can recognize that being in nature is also an obvious source of mental health benefits. Anyone who visits one of Cincinnati’s parks regularly can attest that breaking away from noise pollution and artificial light helps improve focus and reduces anxiety. According to the Harvard School of Public Health, being in nature can also lead to “lower blood pressure and reduced risk of chronic disease” because “green-space exposure is linked to more playtime and less screen time.”

Luckily, Cincinnati is known for its plethora of park options. Whether one is looking to be immersed in greenery in Mt. Airy Forest or looking for a blend of nature and urban design like Smale Riverfront Park, Cincinnati has something for everyone.

This city believes in the power of retreating into nature but also believes in the importance of preservation and promoting environmental stewardship. The effects of the climate crisis are already here. In Cincinnati, we are experiencing stronger, more frequent storms and more consistent precipitation, meaning a higher threat of flooding and water supply contamination. The City of Cincinnati reported that “in 2019, large rain events caused hillside instability along Columbia Parkway.” It cost the city two years and $17.6 million, not because they just wanted to fix the parkway, but because they needed to build with the prevention of future landslides in mind. We are facing a long journey of climate change, but not as passengers, rather as drivers with decisions to make.

Adding to Cincinnati’s long-standing efforts to be a more sustainable city, the 2023 Green Cincinnati Plan emphasizes sourcing local food from regional agriculture, increasing food access and expanding the city’s use of renewable energy. In February, the City of Cincinnati announced the continuation of the Green Cincinnati Plan by opening this year’s grant applications. They will be “investing at least $300,000 this year in dynamic, neighborhood-level solutions to the climate crisis.”

Like an artist carefully selecting their materials and refining their craft, we must make choices that protect and enhance the ecosystems of which we are a part. Reducing our plastic use, switching to reusable items like grocery bags and glass containers, conserving energy and water, using public transportation or cycling, and minimizing overconsumption are all helpful steps toward sustainability and protecting nature. There are many ways to reduce our carbon footprints as individuals. However, it’s important to recognize that policy and legal protections of our precious resources will ultimately lead to a more successful, sustainable future.

The Ohio River serves as a reminder of our impact on the environment and our potential recovery through collective action and policy change. As we continue to confront the effects of climate change, we have to continue examining our relationship with nature. Art, music and coming together as a community are crucial to processing these stark facts about the climate crisis.

Artists like Fleming remind us of Nature’s beauty and fragility, giving us a sense of awe and reverence as audience members. It is this connection that can inspire action. People created these problems, and together, people can solve them.

With our individual and collective commitment to sustainability and stewardship, there is hope for revitalizing our ecosystems and protecting the resources that sustain us. We have to keep gathering, staying informed and talking about these issues, and keep our elected officials accountable. Nature and the arts are places for respite, but more importantly, they are places to find resilience.

Visit the Ohio River Foundation’s website for resources on how to volunteer and donate to the preservation of the river and its ecology: ohioriverfdn.org. And learn how indigenous peoples of Ohio, Kentucky and Indiana continue to advocate for native sovereignty and environmental preservation: UrbanNativeCollective.org.