Kindred musical spirits

by Ken Smith

Apart from their given name, composers James MacMillan and James Lee III have a couple of other things in common. First is a shared background in both orchestral and choral music; second is a connection to conductor Juanjo Mena dating back to 2012.

Before his May Festival days, Mena led the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra in Lee’s Sukkot Through Orion’s Nebula, “a wonderfully rich series of contrasts that was warmly received by the CSO musicians,” the conductor recalls. Lee, too, was amazed at the vibrancy Mena achieved through the orchestral ranks. “Even the tuba player was excited about how I explored the low notes,” he exclaims.

But when Mena reached out to Lee with a commission for the May Festival’s 150th anniversary season, the Baltimore-based composer was, frankly, surprised. “I’ve written a lot of choral music, mostly for the Baltimore Choral Arts Society,” he says, “but nearly all of my commissions have been for orchestral music.”

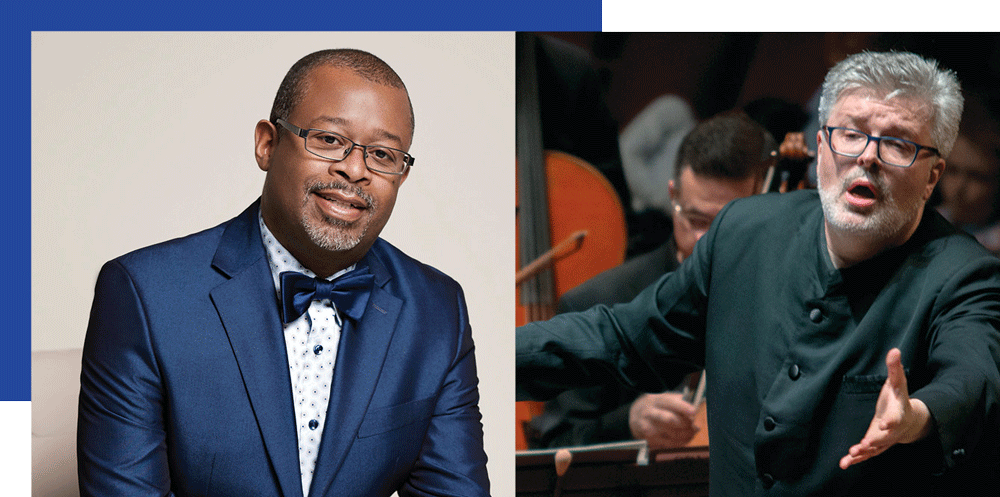

A decade ago, Mena had taken Lee’s Sukkot to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and was astonished by how much he’d refined the piece after hearing it in performance. With Lee’s May Festival commission, Breaths of Universal Longings, he decided to jumpstart the process with a preview at the American Choral Directors Association’s annual conference last February (pictured above). “We both agreed it would be helpful to have as much preparation as possible,” Mena says. “I thought his new work would be similar to the earlier piece, but he surprised me. With voices, his musical ideas are very different, the orchestration is very different. It is a completely different language, but still very special.”

MacMillan first met Mena when he conducted the 2012 world premiere of the composer’s Credo at the BBC Proms. Before the ink was even dry on Mena’s May Festival contract, the conductor was plotting to bring MacMillan, who became a Festival Creative Partner in 2019, to Cincinnati. “I remember this wonderful concert with many local choruses,” the composer says. “Church choirs, children’s choirs, volunteer community groups, all performing at a very high level. It was a sign of how deeply Cincinnati’s choral tradition was rooted.”

So, too, did composer and conductor recognize each other as kindred musical spirits. Much as MacMillan grew up in a British coal-mining family, with a brass-band tradition on one hand and a Catholic church choir on the other, Mena came of age in northern Spain with a strong civic choral tradition of mostly farmers and factory workers. “There are at least two different MacMillans,” Mena says, “the calm religious man, and a social figure of working people. I knew immediately he must return for the Festival’s 150th anniversary.”

Where Lee recalls only minimal guidance regarding his commission (“They mentioned something about the collective universality of human joy,” he says), MacMillan explored texts concerning the power of music, settling on John Dryden’s Alexander’s Feast, a poem also set by Handel.

Although MacMillan’s Timotheus, Bacchus and Cecilia ends with the patron saint of music, the first two sections are distinctly secular. Timotheus, the musician accompanying Alexander on his military campaigns, gives way to Bacchus, the god of drunkenness. “After Alexander’s attacks, the looting soldiers lose all control,” the composer explains. “Some things never change, like the slaughter of Ukrainians today. It shows that music’s power often has a dark center.” But the piece finds resolution in St. Cecilia, he says, culminating in a glorious celebration of music itself.