By Looking Backward, May Festival Springs Forward

by Hannah Edgar

The Festival’s 150th anniversary honors its history and informs its future.

The story of the May Festival is, in some ways, the story of Cincinnati itself. At the time the Festival was founded, Cincinnati was a booming city of nearly 250,000, its perch at the crossroads of America making it a crucible for industry and significant wealth. The city already hosted scores of amateur choirs—disproportionately many for a city of its size—and its first music school, the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music.

That story is still unfolding. The May Festival has reached its 150th year, and many of the elements that made its 1873 maiden voyage a success are still with us: the presence of world class musical institutions (the Cincinnati Conservatory is now, of course, CCM), civic support, and a bevy of choirs in the metro area. Cincinnati remains the only American city selected to host the World Choir Games, in 2012, at which point “City That Sings” was auditioned as a city motto. Taken from the final stanza of a crowdsourced poem, a monument in Cincinnati’s Freedom Park likewise implores passersby to “Sing the Queen City.”

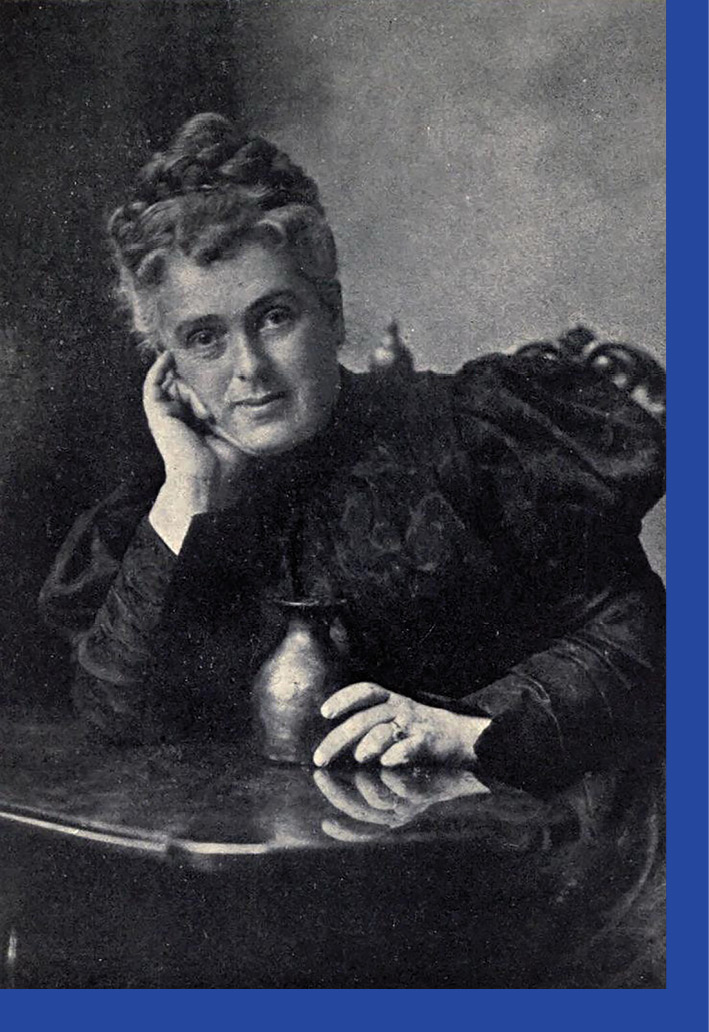

The seed for the May Festival is broadly agreed to have come from Maria Longworth Nichols (later Storer), who later founded Rookwood Pottery. At the time, Nichols was a 23-year-old heiress of the Longworths, who built their wealth from real estate and America’s first successful winemaking business. A trip to London introduced Nichols to grand English choral festivals, and she wanted Cincinnati to have its own.

In 1872, Nichols managed to get an audience with German-American conductor Theodore Thomas, one of America’s greatest musical celebrities, while his celebrated orchestra was touring in Cincinnati. Impressed by Nichols’ sophisticated musical taste and organizational savvy, Thomas agreed to take part.

Remarkably, more than 700 singers participated in the first May Festival. Thomas’s ensemble was enlisted as the Festival orchestra; the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, founded in 1895, would not take over until 1906, after Thomas’s death. Thomas himself served as the May Festival’s first music director, and Carl Barus—a leading figure in Cincinnati’s German musical circles and the maternal great-great-uncle of author Kurt Vonnegut—as its first choral director. Start to finish, the first Festival cost $42,000, according to Charles Frederick Goss’s history of Cincinnati.

The first May Festival featured eight sold-out concerts spread over five sequential days, from May 6 to 10, 1873. Until 1967, the Festival happened biennially, with few exceptions. These days, the May Festival happens every year and features four programs spread out over two weeks. But its roots in those early years still nourish the Festival’s present direction, 150 years on.

A Mirror on the Queen City

Before the May Festival’s founding, group singing in Cincinnati largely reflected one of two dominant styles: English or German. The first to take root in the city, English choral societies tended to be more formal, growing out of church choirs and prioritizing artistic excellence. In contrast, the German choral tradition was mostly centered on community-building and recreation, gathering singers to revel in biergartens or put on light operas.

Cincinnati’s significant Anglophone and Germanophone populations made the city a unique hotbed for both traditions. However, they rarely interacted with one another, save a few early attempts to bridge both communities.

The May Festival would represent the most successful attempt yet to blend the city’s English and German choral strains. After assembling an executive committee, the organizers of the first May Festival circulated a call for singers, printed in German and English, which reached 144 music societies, 1,200 newspapers, and more than 120 music stores. Most of the musicians and repertoire were German, but the May Festival’s leadership team were all English-speaking—a dynamic that was not without friction in the Festival’s early years.

Some key moments in the May Festival’s history likewise reflected the city’s changing demographics. R. Nathaniel Dett became the first Black composer featured1 in the May Festival when it premiered his The Ordering of Moses oratorio in 1937. The piece was rapturously received; a Musical Courier review described its ovation as “pandemonium” and singled it out as “one of the most delectable items…[of the Festival’s] 1937 musical feast.” The work has remained in the Chorus’ repertoire since: In 2014, former May Festival Music Director James Conlon led critically acclaimed performances in Carnegie Hall, and this year Marin Alsop conducts the oratorio in her Festival debut. At the following Festival, in 1939, the May Festival also premiered an oratorio by a local rabbi, James G. Heller (Watchman, What of the Night) , the most visible onstage representation yet of Cincinnati’s historic Jewish community.

Last year, the May Festival reached a new milestone when it prepared the first Spanish-language works in its history: Antonio Estévez’s Cantata Criolla and John Adams’ El Niño. That, too, was very conscious: The Latine population in Cincinnati is among the city’s fastest-growing demographics. Principal Conductor Juanjo Mena, himself a Spanish speaker, spoke, in the 2022 Festival program book, about the importance of including these works. “We were thinking about diversity and the different cultures that we have also in Cincinnati,” Mena said. “Why not move the programming a little in this area?”

Although this May Festival is Mena’s last, Executive Director Steven Sunderman says that the civic-minded ethos he nurtured is here to stay.

“I have to give a shout-out to Juanjo, because a big focus for him has been involving the community in the May Festival and centering other traditions,” he says.

A Zest for Premieres

The first May Festival was so ambitious that it ran $350 in the red, paid for by its executive committee. By 1878, however—the third May Festival, and first in its new digs at Music Hall—it netted an amazing $30,000 profit. Festival organizers funneled part of that sum toward founding the very first composition competition in the United States. Winners received a $1,000 cash prize and had their works performed at the May Festival.

The unnamed competition lasted only two Festivals, but the winning works established the May Festival’s investment in nurturing new repertoire early on. The May Festival has given 35 world premieres to date, among them a revised version of Bernstein’s Symphony No. 3, Kaddish (2002) and an incomplete Liszt oratorio (St. Stanislaus, 2003). This season alone, the May Festival welcomes three new commissions, all by names familiar to Cincinnati concertgoers in recent seasons: James MacMillan’s Timotheus, Bacchus and Cecilia (May 19), James Lee III’s Breaths of Universal Longings (May 19), and Julia Adolphe’s Crown of Hummingbirds (May 25).

The May Festival’s early-established musical excellence also made it an ideal testing ground for works performed in Europe but never attempted by American ensembles. The May Festival gave the American premiere of Bach’s Magnificat in 1875, during its second year. The sesquicentennial season commemorates this achievement by including it in the same opening program with the MacMillan and Lee commissions.

But the May Festival’s most ambitious commissioning project this year wasn’t for the May Festival Chorus at all. Rather than “patting ourselves on the back and having a big party for our own constituency,” per Sunderman, the Festival collaborated with students and alumni of Luna Composition Lab—a mentorship program for young composers who are female, nonbinary or gender nonconforming—to gift 25 new works to 25 choirs in greater Cincinnati. Dubbed “25 for 25,” the program brought ensembles together to debut their works at a March 19 showcase at Christ Church Cathedral, with a few other premieres presented independently this spring and next. (Read more about this project)

“A lot of the choirs had never commissioned anything before, so working with a composer was new for them. I think they grew from that, and I think the composers grew as well, working with somebody on the other end of the telephone or the Zoom screen,” Sunderman says. “We all know a rising tide lifts all boats. When one group gets better, the rest of the choral community gets better.”

A True Community Chorus

“25 for 25” nods not only to the May Festival’s rich commissioning history but the Chorus’ status as a true community ensemble. The May Festival Chorus is famously all-volunteer; when conducting the ensemble in 1973 for its centennial year, Leonard Bernstein mused that “one of the most valuable features of Cincinnati’s Festival as I see it is that it preserves the involvement of the community chorus…. I’m filled with admiration at what they accomplish.”

Indeed, all 36 choral societies in Cincinnati were invited to participate in the first May Festival in 1873, as were choirs from a few other towns in Ohio. The Festival set exacting expectations for the chorus from the beginning, tracking rehearsal attendance through punch cards. Three unexcused absences would be grounds for dismissal from the chorus.

The exhaustive preparation wasn’t lost on anyone who heard that first Festival. Press coverage breathlessly declared Cincinnati “the first musical city of the West.” The Chicago Tribune echoed the plaudits of other publications and posited why Cincinnati was able to pull off a cultural achievement unimaginable in other cities: “It is only an old and stationary population of leisure and wealth which can produce such a chorus…. Cincinnati had the material at home, and its singers submitted to a drill and discipline which were rigidly severe.”

After all, not too many choruses would tackle Gustav Mahler’s monumental Symphony No. 8, sometimes dubbed “the Symphony of a Thousand,” as frequently as the May Festival Chorus has. The grand finale performance on May 27 with the Cleveland Orchestra Chorus, May Festival Youth Chorus, Cincinnati Boychoir and Cincinnati Youth Choir marks the May Festival’s 10th performance of Mahler’s Symphony No. 8. Director of Choruses Robert Porco has prepared Mahler 8 six times for the May Festival alone—as many times as the New York Philharmonic, the nation’s oldest orchestra, has performed the epic work over its entire history.

“It’s become a little bit of a tradition,” Sunderman says.

So has Mahler’s music more broadly, including his other two symphonies that involve chorus. His Symphony No. 3 is among those works that received its American premiere at the May Festival, in 1914. And when, at long last, Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra performers and audiences returned to full capacity at Music Hall earlier this season, Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 was selected to mark the occasion.

In this way, the 150th anniversary honors the May Festival’s more recent history, too, while keeping its gaze clearly fixed on the future. And who knows what that future might hold?

“We’re not just looking back. We’re using the last 150 years as a jumping-off point into the next 150 years,” Sunderman says.