Beginnings of the Cincinnati May Festival and Music Hall

by Craig Doolin, co-author of A City That Sings: Choral Music in Cincinnati

Cincinnati’s famous May Festival, first held in 1873, is a unique mixture of choral traditions. While the artistic forces were almost entirely German, the administrative team that planned the event was mostly of English descent. Cincinnati’s successful 1870 Saengerfest, with its 1,800 singers, was certainly a hometown model for the May Festival, but the tone of the event came from the spectacularly large, but well-mannered, display of the massed-choir traditions of English festivals in Leeds and elsewhere. The festive social component of the German festivals, complete with food and drink, hasn’t been a regular part of the May Festival. At the time of this writing, the Festival is 150 years old and has been a continuous event since its inception in 1873. Until 1967, the May Festival was held every two years with only a few exceptions, but since then it has been given every year.

Courtesy of the Friends of Music Hall

Over the years, many people have led the May Festival, including Theodore Thomas, Eugène Ysaÿe, Eugene Goossens, Josef Krips, Max Rudolf, James Conlon and, presently, Juanjo Mena.

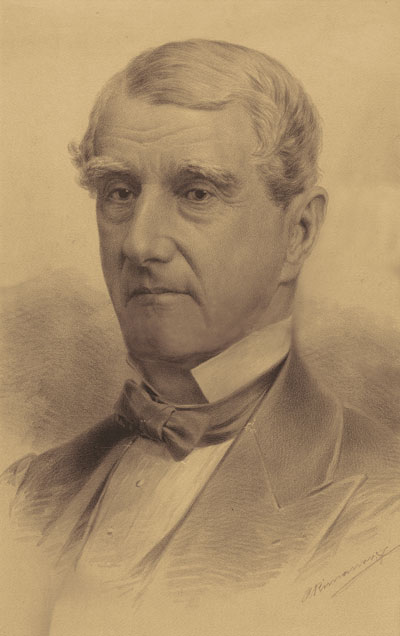

Cincinnati history holds that Maria (pronounced with a long “i”) Longworth Nichols, the 23-year-old granddaughter of the wealthy Nicholas Longworth, invited the famous conductor, Theodore Thomas, to her home on Grandin Road to ask him to create and conduct what is today the oldest continuous choral music festival in the Western Hemisphere. Also present at this historic meeting were Maria’s husband, Colonel George Ward Nichols, who had been an aide-de-camp to Civil War Generals Fremont and Sherman; Heinrich Rattermann, a leading figure in the Saengerfests of the past decade; and Henry Krehbiel, music critic of the Cincinnati Gazette.

Maria’s eagerness to have a festival in Cincinnati came from an 1871 trip to England, where she witnessed one of the large English festivals. Thomas, during their meeting in 1872, agreed to be conductor of the festival if $50,000 could be raised for a guarantee fund and a committee could be formed to take care of the business aspects of the event.

The Cincinnati Musical Festival Association’s Executive Committee included, among others, George Ward Nichols as President, with dry goods merchant John Shillito as treasurer, Cincinnati music publisher John Church as Chairman of the Printing Committee, and attorney Bellamy Storer, Jr., as Secretary. Over the following eight months, these men made all the business decisions leading to the May Festival of 1873.

They decided to hire Theodore Thomas as musical director and Carl Barus as director of the chorus. Thomas’s touring orchestra would play, as they would continue to do at every Festival until 1904. Arthur Mees, a Cincinnati music teacher, was named rehearsal accompanist and, later, Festival organist. Choristers were assembled from throughout the West (today’s Midwest) by distributing a circular to 121 music dealers, 60 post offices, and 144 singing societies. The circular was also distributed to 1,120 newspapers throughout Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, and “the leading papers of the West.” Rehearsals were set to begin in January of 1872.

Sometime in November, the Executive Committee engaged soloists. The soloists for the 1873 May Festival were Mrs. H.M. Smith of Boston, soprano; Emma Dexter of Cincinnati, soprano; Annie Louise Cary, contralto; Nelson Varley, tenor; J.P. Rudolphsen, bass; and Myron W. Whitney, bass. Although Thomas had no advance notice of the soloists’ hiring, he was nonetheless satisfied. He did express concern about Annie Louise Cary, the contralto soloist hired to sing excerpts from Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice:

I must be sure that a good contralto is engaged who can sing the two arias and the recitatives connecting the choruses. She must have a good voice and not be spoiled by singing Trovatore and Lucrezia, and one who will not try to cover up her bad singing by shaking her body and smiling at young America.

However, Thomas relented and later praised her as “perhaps the finest alto voice in the country.”

In the meantime, the Festival chorus was taking shape, and rehearsals were strict. Choristers who were absent from rehearsals had their names published in the local newspapers. By the time the first performance took place, the chorus had 706 members.

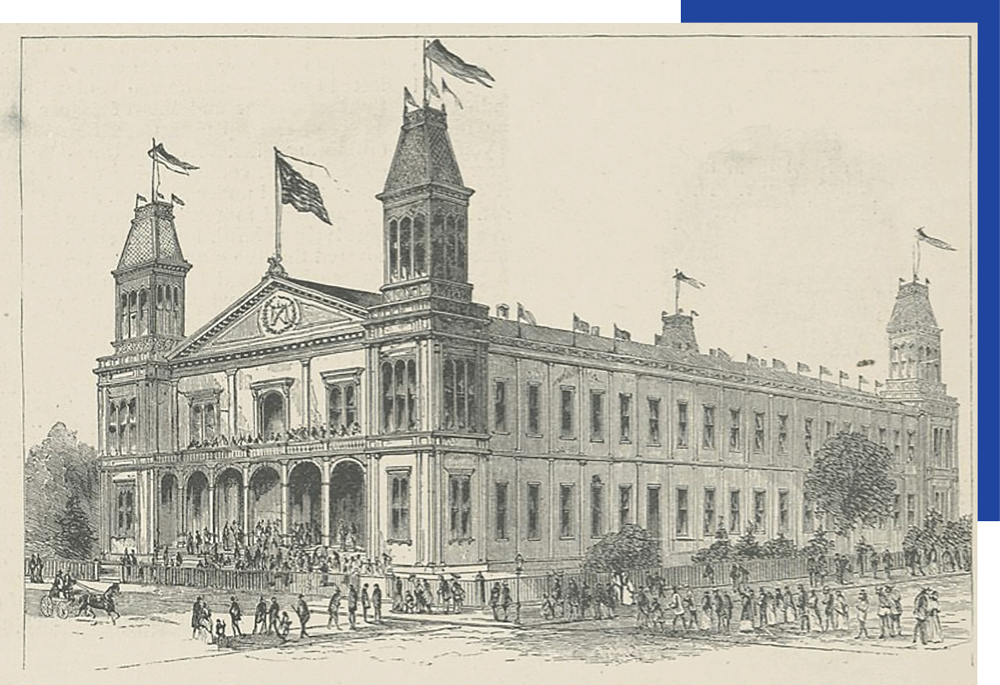

The performances of the 1873 May Festival, held in Saengerfest Halle (built for the 1870 Saengerfest and located on the site where the current Music Hall was built in 1878), established it as the principal musical event of Cincinnati’s concert season, an honor that it retains to the present day. The repertoire was overwhelmingly German. Of the 60 works on the seven concerts, only five were by composers not born in a German-speaking country. The matinee concerts consisted largely of arias, art songs and light orchestral works, including isolated movements of symphonies, Strauss waltzes, and overtures. Thomas’s evening concerts were more formal and consisted of major vocal and choral works, including Handel’s Dettingen Te Deum, scenes from Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice, and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. In the five days from May 6 to 10, 1873, Cincinnati’s reputation as a city of Saengerfests grew to include world-class performances of canonic works for orchestra and chorus.

After the death of Theodore Thomas in 1905, the 1906 May Festival featured British composer Sir Edward Elgar conducting the American premiere of his oratorio The Dream of Gerontius at the final concert. He conducted the second, fifth and sixth concerts of the Festival, and spent the preceding two weeks rehearsing his music with the performers.

Leonard Bernstein was Honorary Music Director for the 1973 centennial celebration of the May Festival, at which he conducted Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis.

The May Festival has presented many world and U.S. premieres in its 150-year history. Among the Festival’s U.S. premieres are Handel’s Dettingen Te Deum (the very first work performed at the very first Festival), Mahler’s Symphony No. 3, Britten’s “Choral Dances” from his opera Gloriana, and Menotti’s The Death of the Bishop of Brindisi.

Continued commissions and artistic innovations ensure that the May Festival remains as relevant today as it was in 1873. The tradition lives and expands.

MUSIC HALL

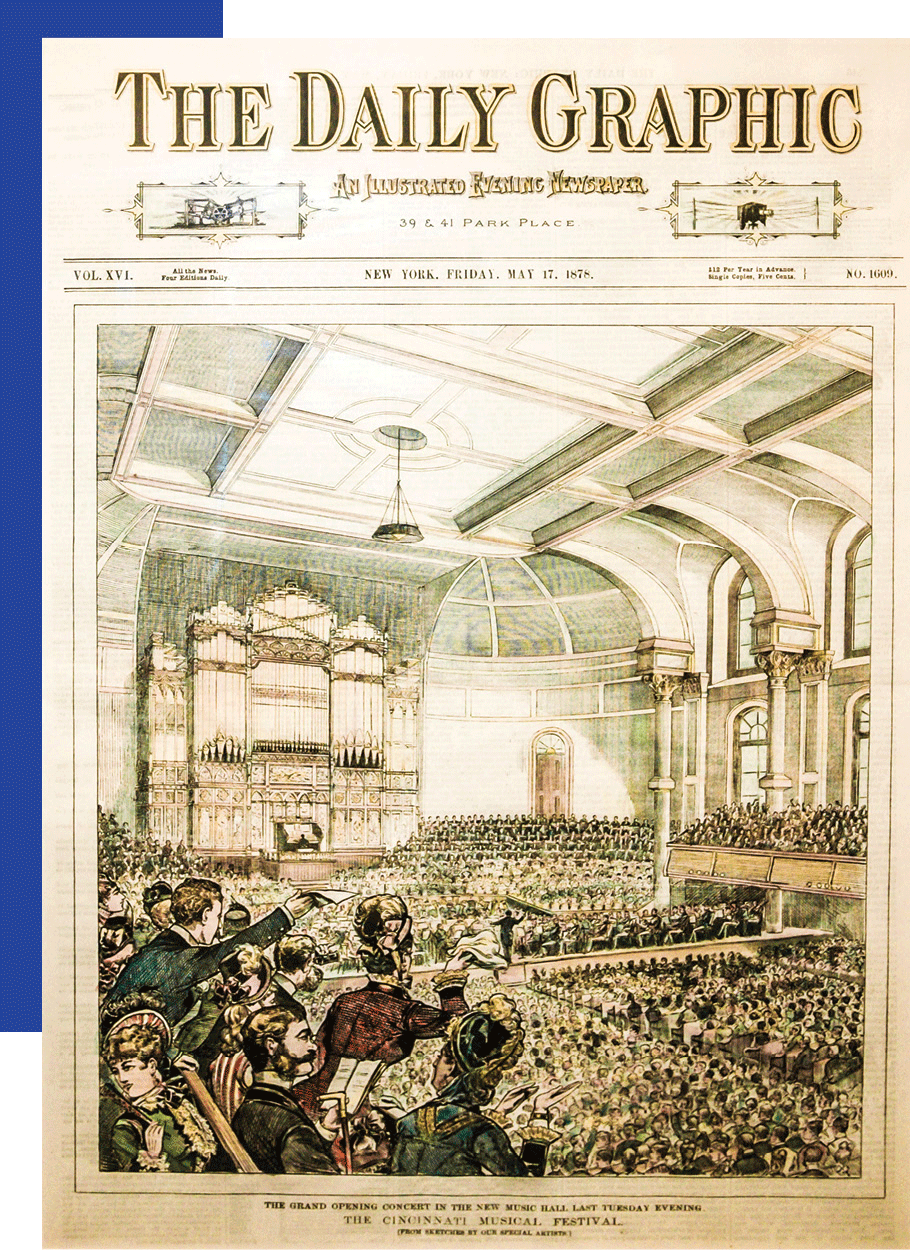

Cincinnati Music Hall is a direct result of the 1875 May Festival. Cincinnati’s usual springtime thunderstorms pelted the leaky tin roof of Saengerfest Hall with rain and hail. The cavernous hall acted as a resonating chamber, and Thomas had to stop the concerts on more than one occasion to let the storms pass. It was also hot and crowded. Windows were broken to reduce the temperature, but the 6,000 attendees, a third of them outside the hall, could not be moved.

Kentucky-born grocer Reuben Springer was so annoyed by the situation that he made the initial $125,000 donation to create a matching fund to enable the construction of Music Hall, completed in 1878. The Third May Festival, originally scheduled for 1877 but postponed until the new hall could be finished, cemented the Festival as a recurring event deserving of notice on a national level.

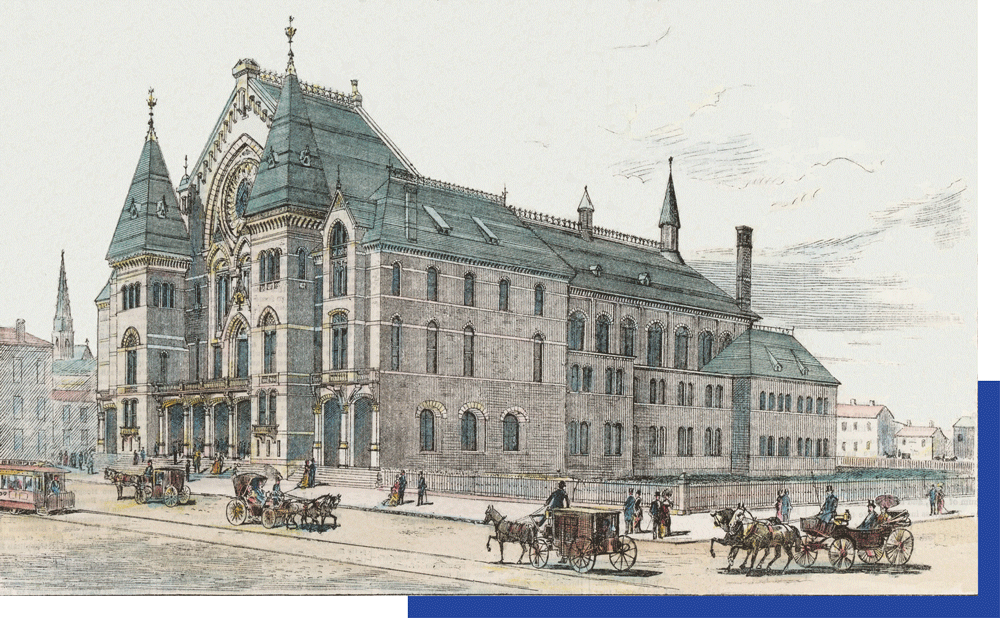

Courtesy of the Friends of Music Hall

Music Hall was designed by Hannaford and Procter and is 150-feet tall at its central gable. Of its 372 feet of frontage, 178 feet would be devoted to the main hall, while nearly 90 feet would be occupied by each of the two exposition buildings, constructed in 1879. Music Hall would be 293 feet deep from Elm Street to the Miami and Erie Canal that flowed behind the hall.

Cincinnati’s Music Hall was officially dedicated at the first concert of the 1878 May Festival on May 14.